AFWG shall not bear any responsibility for any content on such sites. Any link to a third-party site does not constitute an endorsement of the third party, their site or services. AFWG also makes no warranties as to the content of such sites.

Would you like to continue?

Dr Jean Sim1, Dr Limin Wijaya2 and Dr Ban Hock Tan2

1Senior Resident and 2Senior Consultant, Department of Infectious Diseases, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), a well-known cause of life-threatening infection in immunocompromised patients, has been reported to complicate a viral infection in immunocompetent hosts.1-3

A 42-year-old man presented with a 4-day history of fever, productive cough, rhinorrhea and pharyngeal pain. He was a chronic smoker (10 pack-years) and a social drinker, with minor coronary heart disease and asthma on inhaled salbutamol. He was not diabetic and an HIV screen was negative. He was not on systemic steroids or traditional medications.

On admission, he was febrile but hemodynamically stable and was saturating well on room air. The chest was clear to auscultation and a chest X-ray (CXR) was normal. The procalcitonin was 0.26 μg/L (normal value <0.50 μg/L), white blood cell count (WBC) was 5.29 x 109/L and the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) was 0.99 x 109/L (reference range 1.0-3.0 x 109/L). He was diagnosed with upper respiratory infection and treated symptomatically. A throat swab was positive for influenza B.

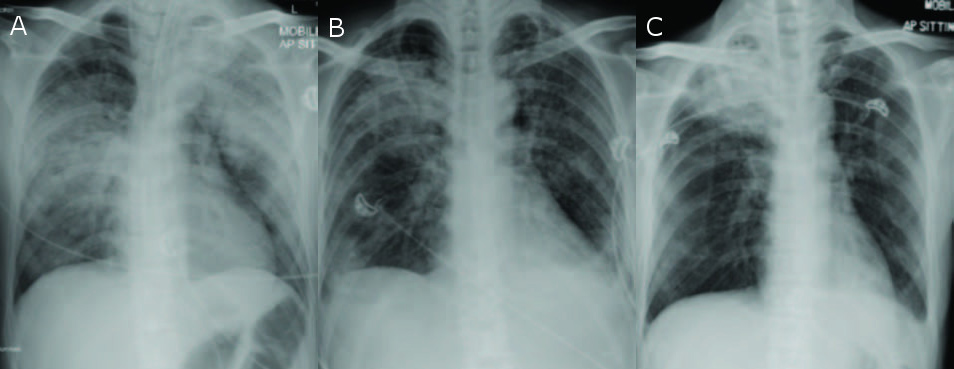

He remained febrile on days 1 to 3 of admission and reported increasing breathlessness. On day 3 of admission, he developed respiratory failure and hypotension requiring vasopressor support. A repeat CXR (Figure A) showed new extensive consolidation bilaterally. Repeat procalcitonin was now 9.0 μg/L, WBC now 8.96 x 109/L and ALC was 0.29 x 109/L. A bronchoscopy (BAL) was performed, which showed purulent secretions with erythematous airway mucosa. He was given broad-spectrum antibiotics and oseltamivir. As his respiratory status continued to deteriorate, he was intubated. Investigations from the BAL were negative except for a galactomannan level of 1.33 (reference range 0-0.49 Ag Index). The serum galactomannan was 0.15 (reference range 0-0.49 Ag Index). Serial CXRs continued to show improvement (Figure B) and he was extubated on day 6 of admission.

He continued to improve but on day 15 of admission, he turned febrile and hypotensive. Investigations revealed a normal procalcitonin level but a WBC of 22.16 x 109/L (96% neutrophils). A repeat CXR (Figure C) showed right upper lobe consolidation. A CT scan of the thorax revealed a mass-like consolidation in the right upper lobe with cavitation.

He underwent transthoracic needle biopsy of the mass. Microbiological tests for tuberculosis and bacterial cultures were negative. Histology showed fungal elements with morphology that was enhanced with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) staining. These were filamentous, uniform in diameter and had acute angle branching, consistent with Aspergillus species. Fungal cultures from his initial BAL grew Aspergillus niger. He was commenced on voriconazole and completed a 12-week course with complete resolution of symptoms and CXR findings.

The first report linking IPA with influenza was in 1952.4 Since then, there have been several reports of IPA complicating influenza.5-8 In these reports, the diagnosis of IPA was usually proven or probable by contemporary criteria, but that of influenza was usually made either by serology or on clinical grounds only. Nevertheless the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 seems to have led to an increase in the number of reports, suggesting that the association cannot be ignored.5,8

Several issues still need clarification. In some reports, aspergillosis and influenza appear to have been co-infections, as in our patient, while in others, IPA appears to have followed influenza. The time of onset may have implications for pathogenesis.

As for reasons for the association, several hypotheses have been put forward, including exposure to several antibiotics (for a non-resolving pneumonia)4 and lymphopenia8. Garcia-Vidal et al suggested that the virus might induce alterations in the bronchial mucosa, hence permitting fungal invasion. The increase in IL-10 in H1N1 infection could also play a role.5

Clancy et al offer some clues that might aid the early diagnosis of this potentially lethal complication.7 From their literature review, they suggest that persistently negative bacterial and viral studies, coupled with the isolation of Aspergillus from respiratory samples in a person with a diffuse and/or cavitary pneumonia should prompt a lung biopsy. In the modern era, how much a role serum and BAL galactomannan could play has not yet been defined.

We suggest that IPA complicating influenza infection is an emerging clinical entity. A high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis and an increase in general awareness amongst medical personnel will aid the diagnosis and prompt treatment of such patients.