AFWG shall not bear any responsibility for any content on such sites. Any link to a third-party site does not constitute an endorsement of the third party, their site or services. AFWG also makes no warranties as to the content of such sites.

Would you like to continue?

Dr Atul Patel

Chief Consultant and Director

Infectious Diseases Clinic

Vedanta Institute of Medical Sciences

Ahmedabad, India

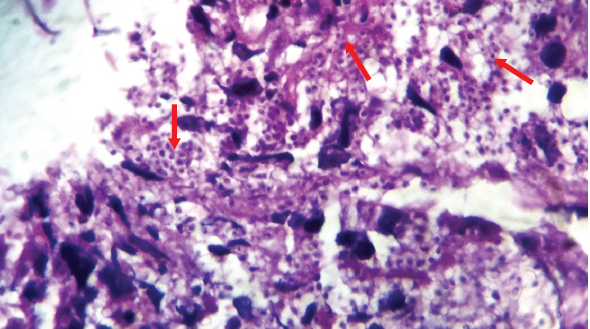

Clinicians overlook the value of direct microscopic examination from a clinical sample and fail to send a request to microbiology laboratory for direct microscopic examination with common stains, including wet preparation potassium hydroxide (KOH) or calcofluor white stains. Direct microscopic examination is cheap and gives you a quick result, which is useful in initiating early therapy with turnaround time of around 30 minutes. Fungal morphology on direct microscopic exam also provide valuable information to clinicians for initiating appropriate antifungal treatment. Figure 2 shows KOH preparation from brain abscess aspirate as an example.

Figure 2. KOL preparation from brain abscess aspirate

When clinicians do not suspect an invasive fungal infection, they can neglect to request for a fungal culture. For instance, a patient with fever of unknown origin, constitutional symptoms, and weight loss with lymphadenopathy along with adrenal enlargement (Figure 3) could be suspected of having tuberculosis (TB) in countries where TB is common like India, but this could also be a case of histoplasmosis. The patient’s clinical profile and imaging results could raise the index of suspicion. A diagnosis of histoplasmosis would be missed unless the histopathologist identifies yeast in the tissue and on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain (Figure 4). Histoplasmosis is a great mimic of TB.

Figure 3. CT scan showing adrenal enlargement

Figure 4. Histopathological examination of adrenal biopsy showing multiple yeast

Drug-drug interactions can affect the efficacy of antifungal agents and some drug-drug interactions can be life-threatening. For instance, co-administration of rifampicin with voriconazole, fluconazole and caspofungin can significantly reduce the plasma concentrations of these antifungals, resulting in loss of antifungal activity. Concomitant use of H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors can significantly decrease the plasma concentration of itraconazole, resulting in treatment failure. Azole antifungal agents could also significantly increase the plasma concentrations of amiodarone, which can lead to serious cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Similarly, azoles increase warfarin exposure and the concomitant use can lead to life-threatening bleeding.

Clinicians must be careful to avoid adding other nephrotoxic drugs in patients, particularly those in the ICU, already receiving amphotericin B. Giving aminoglycosides or other nephrotoxic agents together with amphotericin B could potentially result in severe nephrotoxicity, and renal function should be monitored frequently.

In patients with renal failure and unstable hemodynamics, the dosage of fluconazole may have to be adjusted regularly. This is a common situation in patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis. For example, an ICU patient with acute kidney injury and creatinine clearance of 10–50 mL/min requires 50% of fluconazole dosage. During the ICU course when the patient needs hemodialysis, fluconazole needs to be administered at full calculated dose after hemodialysis. Dose should be halved on the days when patient is not receiving hemodialysis. Hence, dose adjustment in such situation is a continuous process. Higher fluconazole dosage is required along with drug level monitoring in patients who are receiving continuous venvenous hemofiltration.

Clinicians need to be careful when managing critically ill patients receiving azoles and who also have concomitant hypomagnesemia or are also taking quinolones, clarithromycin and other drugs with potential effect on QTc prolongation. These patients could develop arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death. Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring should be the standard of care in ICU patients with multiple risk factors for QTc prolongation.

TDM is a very important component of antifungal therapy in patients with invasive fungal infections and should be encouraged particularly for patients receiving voriconazole, posaconazole and itraconazole. Some clinicians believe that simply using the recommended weight-based dosage of antifungals is enough, and run the risk of treatment failure or drug toxicities. TDM ensures that patients receive the maximum benefit of antifungal treatment.

Mucormycosis is a life-threatening infection, and any delay in effective therapy contributes to morbidity and mortality. Amphotericin B is the usual treatment. Giving posaconazole as oral suspension should be avoided because it will take a week before steady-state level is achieved. In amphotericin B-intolerant patients, posaconazole injection or tablet formulation has better pharmacokinetics than its suspension formulation. In case where clinicians wish to use posaconazole suspension, it should overlap with amphotericin B treatment for at least 1 week before discontinuation of amphotericin B. This ensures patients have uninterrupted antifungal coverage.

In long-term care facilities, isolating Candida in urine is common. However, when an antifungal is indicated, using voriconazole or echinocandins is not recommended because of their poor urinary system penetration.

Candida pneumonia is very uncommon; Candida is generally a colonizer in the respiratory system. Antifungal treatment is not required in these cases.